Playing To Win

Distinguishing How-to-Win from Capabilities in Your Strategy Choice

Utilizing the Can’t/Won’t Test and the Reality Check to Improve Your Strategy

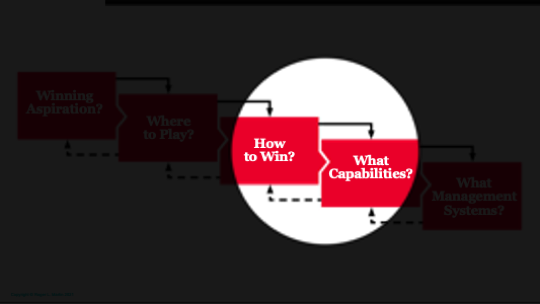

Many people tell me they find confusing the distinction between How-to-Win (HTW) and Capabilities — and I recognize this confusion manifested in the Strategic Choice Cascades that they show me. Is our direct-store-delivery (DSD) system a HTW or a Capability? Is data a HTW or Capability? What about talent? And if we put that in the HTW box, what do we put in the Capabilities box? Aren’t HTW and Capabilities both about winning so why do we need both? Because of all these questions, I have decided to write my 18th Playing to Win Practitioner Insights (PTW/PI) piece on Distinguishing How-to-Win from Capabilities in Your Strategy Choice. (Links for the rest of the PTW/PI series can be found here.)

How-to-Win: The Can’t/Won’t Test

The simplest way to think about your HTW choice is that it is your theory of how you will be better than the competition. That is why simply positing a strength — like a strong DSD system, lots of data or impressive talent is not a HTW. It isn’t a theory of advantage. It just claims that you have that thing. It could actually be a theory of advantage. But that would only be the case if you can specify how it will make you meaningfully better than competition. For that, I use the can’t/won’t test. For your theory of advantage to be robust, you must have a compelling argument as to why either competitors can’t match your advantage even if they want to or won’t match your advantage even if they can.

For example, while a strong DSD system is not a generic theory of advantage, Frito Lay’s DSD system is central to its theory of advantage. It goes something like this: In the salty snacks business, a large cost item is the cost of a shelf DSD system — in which the product is delivered to the store itself (often a convenience store) and placed on the shelf by the delivery driver, who also takes back and accounts for stales. It is labor-intensive and each stop is expensive. Frito Lay has by far and away the largest array of leading salty snack brands (plus some sweet snack ones too): Lays, Doritos, Cheetos, Ruffles, Fritos, Tostitos, Rold Gold, Smart Food and so on. The resulting economies of scale for each DSD truck stop creates a massive cost advantage for Frito Lay that the competitors can’t come close to matching. Plus, it creates a convenience advantage for the store owner of having fewer trucks stopping to stock the shelves. That is a theory of advantage.

While having lots of data is itself not a theory of advantage, WestLaw’s case database and the system that organizes the cases is core to its theory of advantage. Founded in 1882, West Publishing Company started the practice of creating short ‘headnotes’ for cases coming out of the Minnesota court system to enable lawyers to more efficiently sort through cases to determine which were and were not relevant to the legal matter at hand. In due course, West expanded to court cases across the US and created the West American Digest System to classify all cases more formally by key content attributes. In due course, it became the West Key Number System, which is such an industry standard that it is taught to students in law schools across America. In 1975, West Publishing began a journey from a publisher of legal casebooks to the online service, WestLaw, and is now a fully digital, online provider of legal search services, a field it dominates.

WestLaw’s theory of advantage is that it not only has a more comprehensive database of cases than any other provider, but it also has had its staff attorneys writing consistently structured headnotes for the cases for a century, and thanks to those headnotes and the proprietary West Key Number System, lawyers using WestLaw can do faster, less expensive and more accurate searches than in any other way. Competitors can’t match that advantage because it would entail going back a century and creating headnotes for hundreds of thousands of cases and, in addition, creating a search system that is so superior to West Key Number System that it would cause users familiar with the industry standard to abandon and switch. That too is a theory of advantage.

While having impressive talent is not an advantage, McKinsey’s track record of elevating careers produces a talent-based advantage for it. I got a window this advantage the hard way when I attempted to recruit a whip-smart graduating Rhodes Scholar to Monitor Company in the early 1990s. We were a hot shop at the time, and I thought we could win this recruiting battle with McKinsey, who also offered her a job. We got smoked — it wasn’t close. At one point in the wooing process, she asked to speak with other Rhodes Scholars who had succeeded at Monitor Company. Our somewhat embarrassed answer was that she would be the first. McKinsey, in stark contrast, was able to bring multiple of Directors and Principals to their Rhodes recruiting event at Oxford, sending an overpowering message to our joint candidate that the path to success at McKinsey for Rhodes Scholars was clear as a bell, while ours was murky at best.

In due course, I realized that a key part of McKinsey’s theory of advantage was to find new pools of talent first — in this case they discovered the treasure trove of consultant-ready talent at Rhodes House long before the thought occurred to us (in fact probably before we came into existence in 1983) — and ensure the talent from that pool succeeds, and then send that successful talent back to recruit in the pool in question because that makes for the most compelling pitch. If done well, competitors simply can’t catch up in signaling such a secure a road to personal success.

Frito Lay, WestLaw and McKinsey are good examples of theories of advantage by which competitors can’t match. The case of Olay that AG Lafley and I lay out in Playing to Win is a good example of won’t match. Recall that the turnaround strategy for Olay involved building a ‘masstige’ positioning for the brand in the mass channel (e.g., Target, Walgreens, Kroger’s) that featured many of the positive elements of the prestige channel (e.g., Nordstrom, Macy’s, Neiman Marcus). The competitor that could have readily matched our strategy was Estée Lauder, the biggest prestige player. It could have added mass channel distribution to its lowest end prestige brand, the highly successful Clinique line, and probably crushed our attempt to elevate Olay to near-prestige. But we were confident that even though Estée Lauder could have, it wouldn’t because its prestige channel partners would go ballistic, which would be too big a downside — and we were right; Estée Lauder never came.

Capabilities: The Reality Check

If HTW is a theory of advantage that passes the can’t/won’t test, what items should be in the Capabilities choices box? It should include those activities in which you invest to a unique extent or in a unique way that make your theory of advantage a reality.

For Frito-Lay, it continues to invest disproportionately in information technology solutions that make each truck stop more efficient. For example, that has included generations of handheld devices that help the driver plan for each stop, organize the ordered assortment, capture the stales that need to be picked up, and generate the paperwork for the customer. More recently, it has involved developing algorithms based on sales history and store inventory to predict and generate the optimal order for each store.

For WestLaw, it is investing in a veritable army of attorneys (last time I had an inside peek, it was 1500 full time) to write up a headnote for every new case coming out of the US court system to continue to build the advantage of having the best and most intelligently searchable case database. And it is also investing disproportionately in workflow design (a capability shared across all of parent Thomson Reuters online services for professionals) to ensure that the experience of using WestLaw’s online tool is seamless as possible within the existing workflow of its legal clients.

For McKinsey, I have to guess a bit from the outside. But I bet it has invested heavily in the capability of building and managing the careers of its consultants. And I bet it invests disproportionately in finding and exploiting talent pools early. For example, as with its Rhodes Scholar gambit, McKinsey was early into recruiting big at INSEAD as it blossomed from an interesting European executive education center to a leading global MBA program. McKinsey is still the leader by a mile at recruiting there and undoubtedly can bring more successful McKinsey INSEAD graduates to recruiting events than can any other firm.

Of course, as I have written before, organizations must create Management Systems that aid in building and maintaining those distinctive Capabilities that enable the theory of HTW — where organization has chosen to play, in order to meet its winning aspirations. For example, at McKinsey, its meticulously crafted exit program and its comprehensive system for keeping in touch with and supporting its alumni help it maintain its distinctive capability of building and managing the careers of its consultants which contributes to its theory of winning.

Practitioner Insights

Think of your HTW as your theory of competitive advantage. Keep working on it until it can pass the can’t/won’t test. That is, competitors can’t match your advantage, even if it would be very attractive for them to be able to do so. Or competitors won’t match your advantage because the benefit of doing so would be outweighed by detriments experienced elsewhere in their system. Remember to keep tweaking your Where-to-Play in order to create more possibilities for finding a HTW that can pass the can’t/won’t test.

Think of your Capabilities as the key activities in which you must invest disproportionately and perform distinctively to underpin your theory of competitive advantage. A long list isn’t inherently superior to a short one. If the list gets beyond three-five Capabilities, it is likely that you will have listed things in which what you do is indistinguishable in effort and outcome to that of competitors. It doesn’t mean that those things aren’t important. Matching competitors on a range of activities while outperforming them on a few key Capabilities is the key to Playing to Win!